As a backyard chicken keeper who has battled through eight harsh winters in the Midwest, I’ve watched my flock approach the first snowfall of the year with a mix of suspicion and curiosity. I remember looking out the window during the polar vortex of 2024, watching my Rhode Island Red hen, Penny, pecking enthusiastically at a snow drift.

It was -15°F with the wind chill. My heated waterer had failed overnight due to a tripped breaker, and I was sipping coffee, delaying my trek out to the coop. I watched Penny and thought, “Well, at least she’s getting some hydration since the fount is frozen. Nature finds a way, right?”

That assumption almost cost Penny her life.

By that afternoon, Penny wasn’t acting like herself. She was huddled in the corner of the coop, her feathers ruffled up like a pinecone, eyes closed. When I picked her up, her feet were ice cold, and her crop felt like a slushy ice pack. She wasn’t just cold; she was in the early stages of metabolic collapse.

The question “Is it bad for chickens to eat snow?” comes up in homesteading forums every single winter. After nursing Penny back to health—a process that took three days of syringe feeding and a warm bathroom—I learned this lesson the hard way.

The short answer is: Yes, relying on snow instead of liquid water is dangerous for your chickens.

While they can physically eat it, doing so lowers their body temperature, burns critical calories needed for survival, and often leads to severe dehydration.

This comprehensive guide covers everything I’ve learned about winter poultry hydration, the science behind why snow is risky, and the practical, battle-tested solutions to keep your flock healthy when the world freezes over.

Is It Bad for Chickens to Eat Snow? The Science Behind the Risk

When temperatures plummet and water sources freeze solid, chickens instinctively peck at snow. To a new keeper, this looks like a reasonable adaptation. Wild birds do it, right? However, for a domestic chicken, the biological cost of this behavior is incredibly high.

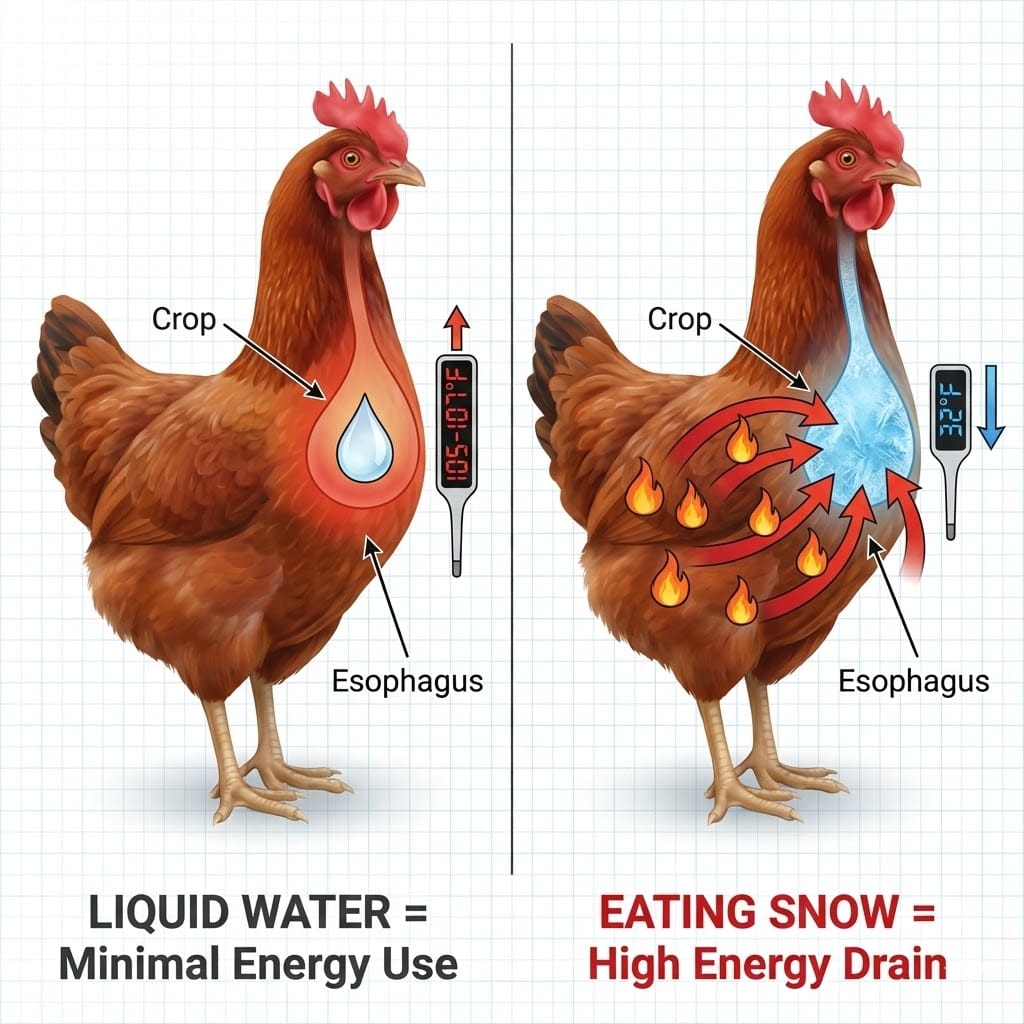

The Energy Cost of Melting Snow

Chickens are endotherms, meaning they generate their own body heat. A healthy chicken works hard to maintain a high internal body temperature between 105°F and 107°F, according to research published by the National Institutes of Health studying poultry body temperature regulation. This is significantly higher than the 32°F or lower temperature of snow.

Furthermore, studies on embryonic temperature manipulation published in Scientific Reports confirm that adult chickens maintain this range (approx. 41-42°C) under thermoneutral conditions. When a chicken eats snow, that frozen matter goes into their crop—a storage pouch at the base of the neck. Before that water can be digested or absorbed into the bloodstream to hydrate the bird, the body must melt it and warm it up to 105°F.

This is a massive energy drain. Here’s why: when something frozen needs to become liquid, it requires a specific amount of energy—physics calls this the ‘latent heat of fusion.’ Your chicken becomes the heater, burning her own calories to generate that heat.

In the dead of winter, your chickens need every single calorie just to stay within their ‘thermoneutral zone’—which research from the Poultry Extension Collaborative identifies as approximately 60-75°F for most poultry, though this varies by age, feather cover, and body weight. When environmental temperatures drop well below this zone, the bird experiences cold stress. If they are burning precious energy to melt a crop full of snow, they aren’t using those calories to stay warm, fight off illness, or produce eggs.

The Hydration Math Doesn’t Add Up

The second problem is volume. Snow, being mostly air in its structure, contains far less actual water than its volume suggests—estimates suggest roughly 10% depending on snow type, though this varies significantly between powder and wet packing snow.

Let’s look at the hydration math: Adult chickens typically drink between one and two cups (8-16 ounces) of water daily under normal conditions, according to industry guidelines from Cackle Hatchery. Laying hens specifically require about 250-300ml according to poultry nutrition research, though this amount can double during hot weather or peak egg production.

Studies published in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database demonstrate that broiler chickens maintain water:feed consumption ratios averaging 1.77 grams of water per gram of feed.

Research from the University of Georgia Cooperative Extension demonstrates how dramatically temperature affects these needs. During cold weather, the water:feed ratio drops to 1.55:1, rises to 1.65:1 in mild weather, and increases to 1.75:1 during hot conditions. This means your winter flock actually needs slightly less water per pound of feed than summer—but they still need liquid water, not snow, to achieve even this reduced ratio.

Additionally, water consumption in broilers increases approximately 7% for each degree Fahrenheit increase in temperature, according to University of Georgia research. While this might suggest chickens need less water in cold weather, this reduction applies only when they have access to liquid water—eating snow reverses this advantage by increasing their metabolic energy expenditure.

To understand the scale of this need, look at commercial data. Research conducted at the University of Arkansas Applied Broiler Research Farm tracking twelve consecutive flocks found that daily water consumption steadily increases from approximately 1 gallon per 1,000 birds at day one to nearly 4 gallons per 1,000 birds by market age. When scaled to backyard flocks, this demonstrates why even temporary water freezing creates an immediate hydration crisis—water needs don’t pause for winter.

To obtain equivalent hydration based on these estimates, a hen would need to consume roughly 85 to 100 ounces of snow—that’s over half a gallon of snow daily. For larger dual-purpose breeds, this increases to 1.25 gallons.

Think about that. Picture a gallon milk jug. Now picture your chicken trying to eat a milk jug filled with snow every single day. Physically, a chicken’s crop simply cannot hold that much volume. It would be packed full all day long, leaving no room for food. Therefore, a chicken eating snow is almost guaranteed to become dehydrated because she simply cannot eat enough of it to meet her needs.

Comparison: Liquid Water vs. Snow Consumption

| Factor | Liquid Water | Snow Consumption |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Required | Minimal (digestive only) | Very High (body must melt ice first) |

| Hydration Efficiency | 100% absorption | ~10% effective volume |

| Body Temperature | Body temp maintained | Core temp decreases rapidly |

| Daily Needs Met | Easily met | Nearly impossible to consume enough |

| Calorie Usage | Normal | Increased metabolic burn |

Research on water deprivation in poultry demonstrates that limiting water access creates measurable physiological stress responses, with reduced performance and health impacts beginning within the first day of restriction.

Why Chickens Eat Snow (Understanding the Behavior)

If eating snow is so inefficient and dangerous, why do they do it?

1. The “Peck First, Ask Questions Later” Instinct

Chickens explore their world with their beaks. When snow covers their familiar run, it changes their environment. They peck at it out of curiosity. I’ve watched young pullets experiencing their first winter treat snow like a fascinating new treat, chasing snowflakes or scratching at drifts.

2. Lack of Thirst Drive

Chickens lack the sophisticated “thirst drive” that mammals have. A dog will seek water when it feels dry; a chicken often doesn’t realize it is dehydrated until the situation is critical. They don’t instinctively know that eating snow will drop their core temperature. They just know their throat is dry, and the snow is wet.

3. The Follow-the-Leader Effect

Chickens are flock animals. If one dominant hen starts pecking at the snow because the waterer is frozen, the others will copy her. I once watched my entire flock of 12 pecking at ice on a puddle, ignoring the fresh water I had just put down five feet away, simply because the head hen was focused on the ice.

4. Desperation

This is the most common reason. If your water sources are frozen solid and you haven’t been out to break the ice since the night before, that curiosity turns into desperation. They are thirsty, and snow is the only moisture available.

Age and Seasonal Factors in Hydration

Not every chicken in your flock faces the same risks. Understanding the difference between your first-year layers (pullets) and your older hens is vital for winter management.

First-Winter Pullets vs. Mature Hens

- Pullets (Under 1 Year): These birds are often the most vulnerable. According to the University of Kentucky Department of Animal & Food Sciences, the body temperature of a newly hatched chick starts lower (around 103.5°F) and stabilizes over three weeks. Young pullets facing their first winter are physiologically robust but behaviorally inexperienced. They typically lay eggs straight through winter, which requires massive amounts of water. A pullet eating snow is trying to hydrate enough to produce an egg and stay warm, leading to rapid metabolic crash. Young pullets experiencing their first winter require special attention, as they haven’t developed full cold tolerance yet. My winter care guide for young chicks and chickens covers age-specific hydration needs, supplemental heat decisions, and growth considerations in cold weather.

- Mature Hens (Molting): Older hens often stop laying in winter to molt (lose and regrow feathers). While they don’t need water for eggs, growing feathers is protein-intensive and requires hydration for blood flow to the new feather shafts (pin feathers). A dehydrated molting hen will struggle to regrow her coat, leaving her with bald spots that are highly susceptible to frostbite.

Seasonal Timing

- Early Winter (Nov-Dec): This is the “training period.” This is when you must train your flock to use heated waterers. They may be afraid of new cords or strange buckets.

- Deep Winter (Jan-Feb): This is the danger zone. The novelty of snow has worn off, but water sources freeze faster. This is when chronic dehydration sets in.

How Snow Consumption Affects Chicken Health

When a chicken relies on snow, the health decline can happen surprisingly fast. It’s not just about being thirsty; it’s a systemic shut-down.

1. Immediate Effects: The Chill Factor

As soon as that freezing snow hits the crop, the bird’s internal temperature drops. The crop sits right against the major blood vessels in the neck and chest. This cold mass acts like an internal ice pack, cooling the blood circulating to the rest of the body.

To protect the vital organs (heart, lungs, liver), the chicken’s body constricts blood flow to the extremities. This means less warm blood goes to the comb, wattles, and toes. This immediate reaction makes the bird significantly more susceptible to frostbite, even if the air temperature isn’t critically low. Frostbite can develop within hours when circulation is compromised by cold stress. Learn how to prevent and treat frostbite on chicken combs before minor cold damage becomes permanent injury.

2. Short-Term Consequences (24-72 Hours)

If snow eating continues for a day or two, you will see a dramatic shift in your flock’s behavior and productivity:

- Egg Production Stops: This is often the first sign. Making an egg requires a huge amount of water. If a hen is dehydrated, her body will reabsorb that liquid to keep her alive, shutting down the “egg factory” instantly.

- Lethargy: The bird will stand in one spot, often puffed up. A puffed-up chicken is trying to trap body heat, but if she’s cold from the inside due to snow, puffing up won’t help enough.

- Pale Comb: The bright red comb turns a dull pink, purple, or grayish color. This indicates poor circulation and low blood volume.

- Reduced Feed Intake: Chickens need water to soften the food in their crop. If they are dehydrated, they stop eating dry pellets because they can’t digest them. This creates a death spiral: they are cold, so they need food for energy, but they can’t eat because they are thirsty. This correlation is so strong that Mississippi State Extension recommends monitoring water meter data daily as the primary indicator of flock health; a drop in water intake almost always precedes a drop in feed intake.

3. Long-Term Risks

Chronic dehydration leads to kidney stress. Chickens produce urates (the white part of the poop) rather than liquid urine. Without enough water, these urates can crystallize in the kidneys and ureters, causing “visceral gout.”

Furthermore, temperature regulation impacts long-term weight. Research from the University of Georgia highlights that birds maintaining optimal temperatures gained significantly more weight than those struggling with hyperthermia or hypothermia. Even if the bird survives the winter, the stress of “eating snow” creates a caloric deficit that results in weight loss and muscle wasting.

The link between water access and overall performance is undeniable. A commercial broiler study published through ScholarWorks found that flocks grown in 2010-2011 consumed significantly more water per bird (190.48 liters per 1,000 head) than historical data, yet achieved better weights and feed conversions. This demonstrates that increased water availability—not restriction through frozen sources—is what drives optimal performance and survival.

4. Loss of Disease Detection Capabilities

Daily water consumption serves as the simplest and most effective tool for monitoring flock health. Research from Mississippi State Extension and the University of Arkansas confirms that drops in water intake almost always precede drops in feed intake, making water meters the ‘early warning system’ for disease outbreaks. When your flock suddenly starts eating snow because their waterer froze, you lose this critical health monitoring capability entirely.

According to Dine-A-Chook’s analysis of hydration requirements, adult chickens require consistently available water to process feed. A loss of even 10% of body water can result in serious physical disorders and a drop in egg production.

How to Feed Chickens in the Snow? Complete Winter Hydration Solutions

This is the most critical part of winter chicken care. You simply must provide liquid water. I have tried every method under the sun—from carrying buckets in a blizzard to high-tech gadgets. Here are the most effective ways to do it, ranked by reliability and effort.

Winter Water Solutions Comparison

| Method | Cost | Temperature Limit | Electricity Needed | Maintenance | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heated Base | $30-50 | -20°F | Yes | Low | Large flocks, harsh winters |

| Black Rubber Tub | $15 | 20°F | No | High (daily breaking ice) | Moderate climates |

| Two-Bucket Rotation | $20 | Unlimited | No | Very High (3x daily) | Off-grid keepers |

| Heated Dog Bowl | $40-60 | -10°F | Yes | Low | Small flocks, easy cleaning |

1. Heated Waterers (The Most Reliable Option)

Heated waterers represent the gold standard for winter chicken care if you have access to electricity at your coop.

Base Heaters These metal platforms plug into a standard outlet and maintain water temperature just above freezing. You set a metal waterer on top. (Note: Never put a plastic waterer on a metal heating base unless the manufacturer specifically says it is safe. I melted a plastic fount my first year doing this—it was a mess and a fire hazard.) These work well down to about 0°F. If you have electricity in or near your coop, this is the safest and most reliable option. For keepers without access to electricity, I’ve written a comprehensive guide on keeping chicken water from freezing without electricity that covers solar options, insulation techniques, and manual methods that work in extreme cold.

Integrated Heated Waterers These are plastic units with the heating element built inside the walls of the container. These are my personal favorite because the heat is surrounded by water, making them efficient.

Heated Nipple Bucket You can buy (or make) a bucket with horizontal poultry nipples and a de-icer submerged inside. This keeps the water clean and liquid.

Safety Note Always use a GFI (Ground Fault Interrupter) outlet or adapter. Barns are dusty and damp; you want the power to cut immediately if there is a short to prevent fires. Secure all cords so chickens cannot peck at them or roost on them.

2. Insulated Water Solutions (For Moderate Cold)

If you don’t have power at your coop, you have to get creative with insulation. These methods work for temperatures down to the high teens or low 20s (°F).

The Tire Trick This is a classic homesteader hack.

- Get an old car tire (ask a local shop, they often give them away).

- Place a black rubber feed tub inside the tire.

- Stuff the gap between the tub and the tire rim with straw, Styrofoam, or expanding spray foam.

- Why it works: The black rubber absorbs sunlight during the day, and the air pocket in the tire insulates the sides. It won’t stop freezing at -10°F, but it keeps water liquid hours longer than a plastic bucket.

Ping Pong Balls Floating 3-4 ping pong balls in a water tub can keep the surface moving every time a chicken drinks or the wind blows. This movement prevents a solid sheet of ice from forming in light freezes (around 30-32°F).

3. The “Two-Bucket” Rotation System (Manual Method)

For keepers without electricity in severe cold, this is the only 100% reliable method. It requires dedication.

- Buy two identical waterers. Keep one inside your warm house (or mudroom) and one in the coop.

- Morning (7 AM): Bring the warm waterer out. Take the frozen one in to thaw.

- Midday (1 PM): Swap them again.

- Evening (5 PM): Empty the coop waterer entirely. A dry waterer cannot freeze and crack overnight.

Pro-Tip: When bringing water out, use warm water (50-60°F), not boiling hot water. According to KROPPER poultry management guidelines, optimal drinking water temperature ranges between 10-15°C (50-59°F), with water above 20°C (68°F) significantly reducing consumption and promoting bacterial growth. Warm water is palatable and helps raise the chickens’ core temperature gently.

4. Strategic Water Placement

Where you put the water matters.

Inside vs. Outside If your coop is dry and well-ventilated, keep water inside to prevent it from freezing as quickly. However, if the waterer spills, you get wet bedding, which leads to frostbite. I prefer keeping water in the run, but in a corner sheltered from the wind. If you’re building or upgrading your winter housing, proper coop design makes water management significantly easier. Explore cold weather chicken coop designs that incorporate protected water placement, insulation strategies, and layouts that minimize freezing.

Sunlight Place black rubber tubs in the direct sun. The solar gain can make a 10-degree difference.

Regional Winter Water Strategies (USA Guide)

Research tracking broiler water consumption across seasonal variations found that by day 21, consumption in warmer seasons outpaced cooler season usage by 6-10 gallons per 1,000 birds daily. However, this doesn’t mean winter birds need less water—it means they’re consuming water more efficiently when liquid water is available. Remove that liquid water and replace it with snow, and efficiency plummets as energy diverts to melting rather than hydration.

Winter in Maine is very different from winter in Texas. Here is how to tailor your strategy based on your location:

Northeast & Upper Midwest (Deep Freeze Zones)

- Challenge: Prolonged sub-zero temperatures and heavy snow loads.

- Strategy: Redundancy is key. If your primary heated waterer fails, the water freezes in an hour. Always have a backup manual fount ready indoors. Keep waterers strictly in the run to avoid coop humidity, which causes severe frostbite in these zones. According to University of Georgia Cooperative Extension, water consumption naturally varies with temperature; ensuring access in these zones is less about fighting heat stress and more about preventing the complete lockout of hydration.

Pacific Northwest (The Damp Cold)

- Challenge: High humidity and hovering-around-freezing temps. It’s wet, not just cold.

- Strategy: Managing humidity is harder here than managing heat. Do not keep water inside the coop; the evaporation will cause mold and respiratory issues. Use horizontal nipples rather than open bowls to prevent spillage and muddy runs.

The South & Southwest (The “Surprise” Freeze)

- Challenge: Chickens are not acclimated to cold, and owners often lack heated gear.

- Strategy: When a rare freeze hits (like the Texas freeze of 2021), your birds are at highest risk because they haven’t grown dense winter down. Since you might not have heated waterers, bring warm water out 3-4 times a day during the snap. Adding electrolytes is crucial here as the stress of the sudden temp drop hits southern birds harder.

Feeding Strategy Connections: Diet for Hydration

You can also “sneak” water into your chickens through their food. This doesn’t replace drinking water, but it helps supplement their intake.

- Warm Mash: In the mornings, I take their regular layer pellets and mix them with warm water until it reaches an oatmeal consistency. The chickens go crazy for it. They eat the feed and get a belly full of warm water simultaneously.

- Fermented Feed: Fermenting feed involves soaking grains or pellets in water for 3 days. The resulting food is swollen with water and probiotics.

- Water-Rich Snacks: Save your kitchen scraps. Cucumbers, melons, and cooked squash are high in water content. Avoid frozen scraps; thaw them first! Winter nutrition requires specific adjustments beyond just hydration. Learn what to feed chickens in winter to maintain egg production, support immune function, and provide the extra calories needed for cold weather survival.

Can You Let Chickens Free Range in the Snow? Safety Guidelines

A common debate among chicken keepers: “Can you let chickens free range in the snow?” or do they need to be locked up all winter?

I believe in letting chickens decide. I open my coop door every day unless it is actively blizzarding. However, there are safety rules. When weighing the pros and cons of chicken runs versus free ranging in winter, safety and shelter availability are the deciding factors.

Temperature Thresholds & Wind Chill

Generally, fully feathered, cold-hardy breeds are safe to roam outside when temperatures are above 20°F. However, wind chill is the real killer. A 30°F day with 20mph winds strips heat from their bodies faster than a calm 15°F day. If the wind is howling, I keep them in the covered run.

Breed Matters

Not all chickens are created equal regarding winter resilience.

Cold-Hardy vs. Cold-Sensitive Breeds

| Breed Category | Examples | Winter Tolerance | Comb Type | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold-Hardy | Buff Orpingtons, Rhode Island Reds, Wyandottes | Excellent (down to 0°F) | Rose or Pea Combs | Can free-range in most conditions |

| Moderate | Plymouth Rocks, Australorps | Good (down to 10°F) | Single Comb (moderate size) | Watch for comb frostbite |

| Cold-Sensitive | Silkies, Leghorns, Seramas | Poor (below 20°F risky) | Large Single Comb or Non-standard | Require covered runs |

Cold-Hardy Breeds Buff Orpingtons, Rhode Island Reds, Wyandottes, Plymouth Rocks, and Cochins. These birds have large body mass, thick feathering, and often smaller combs (like rose combs). They handle snow reasonably well. Buff Orpingtons, one of my personal favorites, are exceptionally cold-hardy. My complete Buff Orpington breed guide covers their winter performance, egg production in cold weather, and why they’re ideal for harsh climates.

Cold-Sensitive Breeds Silkies (their feathers don’t insulate when wet), Leghorns (huge combs prone to frostbite), Seramas, and Frizzles. These birds should be protected from snow and drafts. I often keep my Silkies in a strictly covered run all winter. If you’re still deciding which breeds to add to your flock, my guide to the easiest chicken breeds for beginners breaks down cold tolerance, temperament, and care requirements for new keepers.

Path Clearing Strategies

Chickens generally hate walking in deep snow. Their legs are not designed for it, and they have no feathers on their feet (usually) to keep them warm. If the snow is higher than their hock (their “knee”), they likely won’t leave the coop, leading to boredom and bullying.

To encourage exercise—which generates body heat—I shovel “chicken highways” for them. I clear a patch of ground or a path to their favorite dust bathing spot and throw down some straw, hay, or even wood ash. This gives them a warm barrier against the frozen earth and encourages them to scratch and forage.

Can Birds Eat Snow for Water? (A Comparison)

You might be thinking, “But I see chickadees and sparrows eating snow all the time. Why can they do it?”

This is a great question that highlights the difference between wild survival and domestic health. It is critical to understand that a domestic hen is physiologically very different from a wild songbird, despite both being avian species.

Biological Differences in Thermoregulation

Research indicates significant differences in body temperature regulation between wild passerines (perching birds) and domestic poultry. Wild songbirds maintain even higher body temperatures than chickens—often 108-110°F—and their smaller body mass means they lose heat faster, requiring constant energy intake.

However, the critical difference is that these birds are adapted through millions of years of evolution for survival, not optimized for egg production like domestic chickens. A wild bird in winter is essentially in “maintenance mode”—doing just enough to stay alive until spring. Your chicken, however, has been selectively bred to lay eggs year-round or maintain a heavy body weight, both of which are energy-expensive tasks.

Metabolic Rate Comparisons

Small birds have metabolic rates that are explosively high compared to poultry. A chickadee might eat 35% of its body weight daily just to survive the night. To fuel this fire, they often consume high-fat foods (suet, seeds) found in nature.

Chickens, by contrast, eat a lower-energy diet (commercial pellets) and have a slower “basal metabolic rate.” When a chicken eats snow, the energy dip hits them harder because their metabolism isn’t designed for the rapid-fire heat generation seen in wild birds.

Diet and Hydration Needs

The diet itself dictates hydration needs.

- Wild Birds: Often eat seeds, berries, and insects that may contain some moisture or fats that release metabolic water when digested.

- Chickens: Eat dry, pelleted feed with less than 10% moisture content.

To digest these dry pellets, a chicken’s crop must have liquid water added to it. If the crop is filled with dry food and snow, digestion stalls. The bird effectively starves with a full crop because the food cannot be processed. Wild birds do not face this exact “dry pellet” constraint in the same way.

The Verdict on Natural Instincts

Finally, ornithological observations confirm that even wild birds prefer liquid water. If you place a heated birdbath out in January, you will see it swarmed by local wildlife. They choose liquid water over snow every time because their instincts tell them it conserves energy. Relying on snow is a last-resort survival mechanism for them, not a lifestyle preference—and certainly not a strategy we should force upon our domestic flocks.

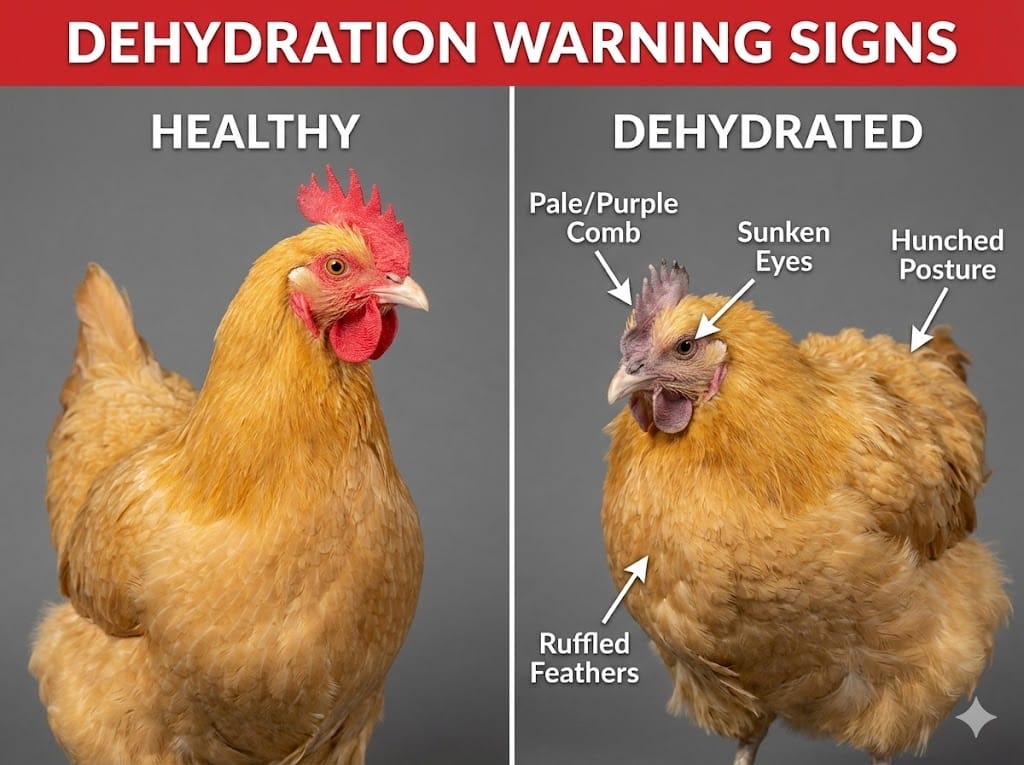

Emergency Signs Your Chickens Need Better Hydration

You need to catch dehydration before a hen ends up like my Penny did. Monitor your flock daily for these signs.

Physical Symptoms

- Sunken Eyes: The eyes look dull or recessed into the head.

- Skin Tenting: This is the best test. Gently pinch the skin under the wing or on the back of the neck. It should snap back immediately. If it stays “tented” or moves back slowly like memory foam, she is severely dehydrated.

- Sticky Saliva: Open the beak gently. The inside of the mouth should be wet. If there are strings of saliva or it feels tacky, she needs water now.

- Dark Comb: The tips of the comb turning purple or black. This is often confused with frostbite, but if the coop isn’t below freezing, it indicates poor circulation due to low blood volume.

Behavioral Changes

- Frantic Pecking: Eating ice or snow aggressively.

- Aggression: Fighting around the waterer when you finally bring liquid water.

- Pant-less Lethargy: In summer, they pant when hot. In winter, they just get quiet. If a bird is sitting alone, fluffed up, and not interested in treats, check her hydration. Learning to recognize these symptoms takes practice. For a comprehensive approach to monitoring your flock’s overall wellbeing, see my guide on performing regular chicken health checks that covers physical examinations, behavioral baselines, and preventive care schedules.

Emergency Triage Protocol

⚠️ Important Veterinary Disclaimer The following emergency steps are first-response measures for backyard chicken keepers while arranging professional care. These suggestions come from my personal experience managing flock health issues and consultations with poultry veterinarians. However, I am not a licensed veterinarian. If your chicken shows signs of severe distress—inability to stand, seizures, completely closed eyes, or non-responsiveness—contact an avian veterinarian immediately. In rural areas without avian specialists, many large animal vets can provide guidance for backyard poultry emergencies.

If you discover a severely dehydrated hen, follow these immediate steps:

Step 1: Provide Gentle Warmth Bring her inside to a room maintained at 50-60°F. Never place a cold chicken directly next to a heat source—the thermal shock can cause cardiac arrest. A bathroom or mudroom works well.

Step 2: Prepare Electrolyte Solution Mix poultry electrolytes into lukewarm water, or create a homemade version using 1 quart water, 2 tablespoons sugar, and 1/8 teaspoon salt. You might also consider using apple cider vinegar for chickens as a natural health tonic once they are stable, though plain electrolytes are best for immediate rehydration.

Step 3: Encourage Drinking (Never Force) Dip her beak gently into the water so she can swallow voluntarily. Forcing water down her throat risks aspiration pneumonia, which is often fatal.

Step 4: Monitor Keep her inside until she is drinking, eating, and pooping normally.

Winter Water Solutions: Preventing Snow Consumption

Prevention is always cheaper than a vet bill. Here is how to set your flock up for success.

Pre-Winter Preparation (Mid-October)

Don’t wait for the first blizzard. By mid-October, you should test all your heated bases. Plug them in for an hour and touch them to ensure they get warm. Stock up on extension cords rated for outdoor use. Check your coop for drafts that might freeze waterers faster. Proper winter ventilation is a delicate balance—too little causes moisture buildup that freezes waterers, while too much creates dangerous drafts. My guide on how much ventilation a chicken coop needs explains the science behind air exchange rates and proper vent placement for winter conditions. Complete winter preparation goes beyond just water management—check out my detailed winterizing chicken coop guide for a comprehensive checklist covering insulation, ventilation, and cold-weather safety measures.

The Daily Winter Routine

During my coldest Ohio winters, my routine looks like this:

- Morning Check: Go out with a kettle of warm water. Top off the heated waterer. Check that the heater is working (touch the water—is it liquid?).

- Midday Observation: Take a quick peek. Are the birds active? Is anyone huddled up? Are they eating snow? If they are eating snow, check the waterer immediately—usually, it means the waterer is empty or frozen.

- Evening Lockdown: Ensure they have water right up until roosting time. Digestion generates heat overnight, and they need water to digest their crop full of corn.

Recommended Product Features

I won’t tell you exactly which brand to buy, but look for these features when shopping:

- Capacity: Get at least 3 gallons for a flock of 8+ birds. Small waterers (1 gallon) freeze much faster than large volumes of water.

- Thermostatically Controlled: Look for heaters that only turn on when temps drop below 35°F. This saves you money on electricity.

- Enclosed Design: Nipple waterers or small-cup waterers are great because chickens can’t dunk their wattles in them. Large open pans lead to wet wattles, which leads to frostbite on the face.

Conclusion

To answer the question one last time: No, chickens cannot safely eat snow instead of water.

It is a myth that “animals know what’s best for them.” My hen Penny didn’t know that eating snow would nearly kill her—she was just reacting to her environment. It is our job as keepers to manage that environment.

While they might peck at the white stuff out of curiosity, relying on snow for hydration is a recipe for hypothermia, dehydration, and stopped egg production. Winter chicken keeping requires adaptation, but with proper water management, your flock will remain healthy, productive, and comfortable regardless of snow depth or temperature extremes.

Remember, a hydrated chicken is a warm chicken. Keep that water liquid, keep it accessible, and your flock will thank you with healthy eggs all winter long.

Share your own winter waterer solutions in the comments below—our chicken keeping community benefits from collective experience across different climate zones!

Oladepo Babatunde is the founder of ChickenStarter.com. He is a backyard chicken keeper and educator who specializes in helping beginners raise healthy flocks, particularly in warm climates. His expertise comes from years of hands-on experience building coops, treating common chicken ailments, and solving flock management issues. His own happy hens are a testament to his methods, laying 25-30 eggs weekly.