⚠️ Medical & Food Safety Disclaimer: This article provides educational information based on poultry management research and personal experience. It does not replace professional veterinary advice. Consult an avian veterinarian for sick chickens or persistent production problems. Follow USDA and FDA food safety guidelines for all eggs. When in doubt about egg safety, discard it.

Introduction

When a chicken lays an egg without a shell, also called a shell-less egg or wind egg, it typically indicates a disruption in the egg formation process within the hen’s reproductive tract. According to poultry specialists at the University of Florida IFAS Extension, this condition often results from calcium deficiency, nutritional imbalances, stress, disease, or reproductive system immaturity in young pullets.

Finding a soft, rubbery egg or a completely shell-less egg in your coop can be alarming for backyard chicken keepers. This is one of several common mistakes first-time chicken keepers make, but fortunately, it’s almost always fixable with proper management. I remember clearly the first time I found one sitting on the pine shavings in the nesting box; it looked like a deflated water balloon and felt warm, squishy, and strangely fragile.

In my seven years of keeping chickens, I’ve handled hundreds of normal eggs, so the texture of a “rubber egg” always stops me in my tracks. While an occasional shell-less egg is usually not cause for panic (often just a “glitch” in the system), repeated occurrences signal underlying health or management issues that require immediate attention.

This comprehensive guide explains the eight main causes of eggs without shells, whether these eggs are safe to eat, proven treatment approaches backed by poultry science, and prevention strategies to restore your flock’s normal egg production.

Understanding Shell-Less and Soft-Shelled Eggs

Before we fix the problem, it helps to understand what is actually happening inside your hen. It isn’t just a matter of “forgetting” the shell; it’s a complex biological assembly line driven by laying hen nutrition and biology.

What Is an Egg Without Shell Called?

You might hear fellow chicken keepers use a few different names for this. Technically, they are often called shell-less eggs (no hard shell at all) or soft-shelled eggs (a very thin, paper-like shell). Old-timers often call them wind eggs or rubber eggs.

Egg Without Shell Weight vs. Normal: You will notice a distinct weight difference immediately. In my experience, you can tell just by holding the carton that something is wrong before you even open it.

- Normal Egg: A standard large egg usually weighs between 58 and 62 grams.

- Shell-Less Egg: According to Mississippi State University Extension, the shell accounts for roughly 10-12% of an egg’s total weight. Therefore, an egg without shell weight usually clocks in lower, typically around 50-55 grams.

What About Eggs Without Shell or Membrane?

Sometimes, you might find what looks like a puddle of yolk and white in the nesting box or on the coop floor, with no casing at all. A chicken laying eggs without shell or membrane indicates a more severe disruption than a simple soft shell.

This “liquid egg” scenario means the yolk was released, but the shell membrane never formed in the isthmus section of the reproductive tract, or the membrane ruptured internally before the shell could form. This is rare and can indicate a more serious acute stressor or internal injury. The isthmus is responsible for adding the two shell membranes over the course of about 1 hour; if the egg rushes through here, you get a liquid mess.

How Normal Egg Shell Formation Works

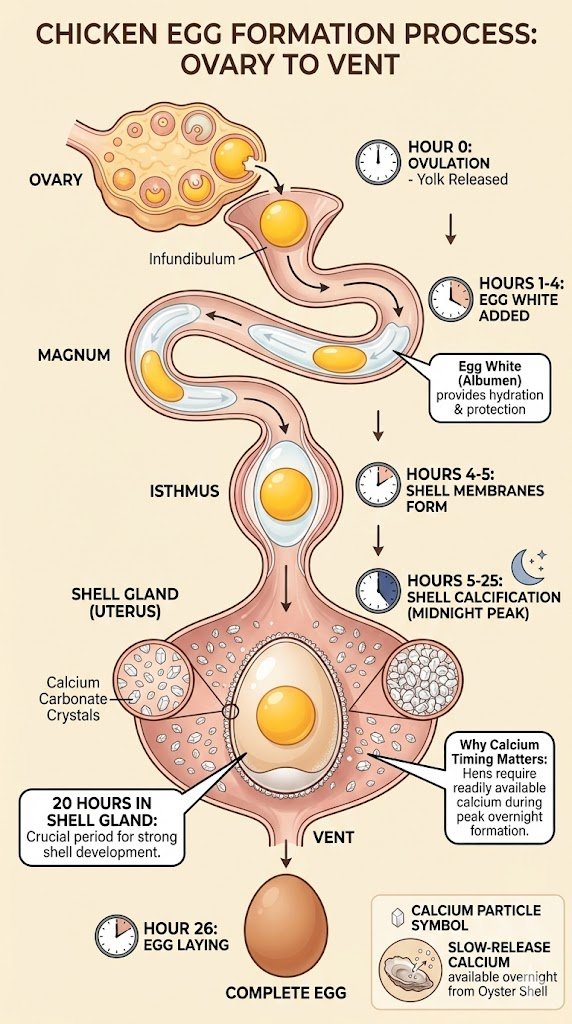

To understand why the shell is missing, we have to look at how it gets there in the first place. The egg travels through a tunnel inside the hen called the oviduct.

According to concepts of eggshell quality from the University of Florida IFAS Extension, the entire egg-making process involves precise timing. While the total formation takes about 24 to 26 hours, the egg spends the majority of that time, about 20 hours, in the shell gland (technically known as the uterus). This process starts over shortly after an egg is laid, meaning a productive hen typically lays an egg every 25-27 hours.

The Midnight Calcification Phenomenon: A critical, often overlooked fact is that eggshell formation generally occurs at night, peaking around midnight. Research from the University of California ANR confirms that “shell formation typically occurs around 12 a.m.” Since chickens do not eat while sleeping, they rely entirely on calcium stored in their crop (digestive pouch) or pulled from their bones to fuel this process.

This is why particle size matters. Fine powdered calcium digests too quickly (often before midnight). Larger particles, like oyster shell, sit in the gizzard and dissolve slowly, providing a steady drip of calcium into the bloodstream exactly when the hen needs it most to print that hard shell.

The Difference Between Shell-Less and Soft-Shelled Eggs

- Shell-less eggs: These have absolutely no hard covering. It is just the yolk and white held together by the shell membrane. It feels like a water balloon. This usually means the egg bypassed the shell gland entirely or spent almost no time there.

- Soft-shelled eggs: These have a shell, but it is incomplete. It feels like parchment paper or a thin layer of chalk. You can dent it with your finger. This usually means the hen tried to make a shell, but ran out of calcium or time.

Quick Comparison: Identifying the Issue

| Feature | Normal Egg | Soft-Shelled Egg | Shell-Less Egg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Weight | 58-62 grams | 55-58 grams | 50-55 grams |

| Appearance | Smooth, hard, uniform color | Papery, wrinkled, dented | Membrane only, transparent/cloudy |

| Texture | Firm, unyielding | Flexible, chalky, rough | Squishy, rubbery, warm |

| Typical Cause | Healthy Production | Mild Calcium Deficiency, Stress | Severe Deficiency, EDS, Immature Gland |

Why Did My Chicken Lay an Egg Without a Shell? 8 Main Causes

Why Does My Hen Lay Soft Shelled Eggs?

If you are asking, “Why does my hen lay soft shelled eggs?”, you are usually seeing the result of a specific disruption in the shell gland. While the causes below detail the specific triggers, the mechanism is always the same: the hen either lacks the calcium carbonate to build the shell, or she expelled the egg before the final 15-20 hours of calcification could occur.

Here are the 8 specific reasons this happens:

1. Nutritional Deficiencies (Calcium, Phosphorus & Trace Minerals)

What causes an egg to not have a shell often traces back to diet. A nutritional deficiency is the most frequent culprit. A laying hen is a high-performance athlete. She needs about 3.5 to 5 grams of calcium every single day (depending on hen size and production level) to produce a hard shell. For a complete breakdown of calcium sources, daily requirements by age, and supplementation strategies, see our comprehensive guide to calcium for chickens.

According to the University of Georgia CAES Extension, nutritional balance is key. If a hen doesn’t get enough calcium from her feed, she will try to pull it from her own bones (specifically the medullary bone). Once that reserve is low, she simply cannot make a hard shell.

The Calcium:Phosphorus Ratio (Ca:P): Proper laying hen nutrition isn’t just about calcium; you also need the right phosphorus balance. The Calcium-to-Phosphorus ratio (Ca:P) is critical, ideally around 10:1 for laying hens (rising to 12:1 in older hens). If phosphorus levels are too high (often from feeding too many scratch grains, sunflower seeds, or table scraps), it hinders calcium absorption in the gut. Even if you feed oyster shells, a phosphorus imbalance can chemically block that calcium from reaching the shell gland.

The Role of Trace Minerals (Zinc & Manganese): While calcium builds the shell, trace minerals like Manganese and Zinc are essential for building the matrix, the protein scaffold that the calcium carbonate attaches to.

- Manganese: Vital for the formation of the cuticle and the matrix. Deficiency leads to thin, translucent shells.

- Zinc: Supports the enzyme carbonic anhydrase, which is necessary for depositing calcium carbonate. Without these minerals, the shell structure is weak, leading to translucent or soft spots even if the bird has plenty of calcium.

Observable Signs:

- Eggs start with thin ends, then become soft all over.

- The hen might look tired or have pale combs.

- You might see her eating her own eggs (trying to get the calcium back).

2. Vitamin D3 Deficiency

You can feed your chicken all the oyster shells in the world, but without Vitamin D3, calcium absorption cannot happen. Vitamin D3 is the “key” that unlocks calcium absorption in the gut. Without it, the calcium just passes right through her digestive system.

Why it happens:

- Lack of sunlight: Chickens absorb D3 through their skin from sunlight. During long winter months or in confined coops, levels drop.

- Dietary imbalance: As noted by Extension.org, adding too many scratch grains dilutes the vitamin intake from formulated feeds, creating a nutritional deficiency.

3. Stress and Environmental Disruption

Chickens are creatures of habit. Any major stress factors can cause what we call “premature expulsion.” Basically, the hen gets scared or stressed, and her body pushes the egg out of the oviduct before the 20-hour shell-making process is finished.

Common Stress Factors:

- Predators: A raccoon or stray dog stalking the coop at night.

- Heat Stress: Temperatures above 85-86°F (30°C) can significantly reduce feed intake and calcium absorption. As documented in the journal Poultry Science and confirmed by Mississippi State University Extension, the hen’s panting alters her blood pH (respiratory alkalosis), reducing the amount of carbonate ions available in the blood to bond with calcium for shell formation.

- Bullying: If a hen is being chased away from the feeder.

My Flock Experience: The “Moving Day” Incident

A few years ago, I decided to move my coop to a shadier spot in the yard. I thought my hens would appreciate the breeze. However, my lead Buff Orpington, Henrietta, hated the change. For three days straight after the move, she laid perfectly intact but completely shell-less eggs. She wasn’t sick, and her diet hadn’t changed. She was just stressed by the new location. Once she settled in, the shells returned to normal. This taught me that sometimes, the “cure” is just patience and routine.

4. Egg Drop Syndrome (Viral Disease)

This is where we get into specific entities that affect flock health. Egg drop syndrome (EDS-76) is a viral infection caused by an adenovirus (specifically adenovirus 127 or Group III avian adenovirus).

What are the symptoms of egg drop syndrome? Unlike a simple nutritional deficiency, EDS usually hits the whole flock, not just one bird. You will see a sudden drop in egg production, along with shell-less eggs, thin shells, and a loss of shell color (brown eggs turning white).

According to veterinary research from the Merck Veterinary Manual, birds with EDS often look healthy otherwise, which makes it tricky to diagnose without a vet.

5. Other Infectious Diseases

Several other illnesses can damage the shell gland (or uterus) directly. Many of these diseases also cause chicken diarrhea and digestive problems, so watch for accompanying symptoms beyond just egg abnormalities.

- Infectious Bronchitis (IB): This is a very common respiratory virus. According to Penn State Extension, even after the chicken stops coughing and sneezing, the damage to the oviduct can be permanent, leading to wrinkled or soft eggs for life.

- Newcastle Disease: This affects the nervous system and reproductive tract. The USDA APHIS warns that this virus spreads quickly and can cause misshapen eggs.

- Mycoplasma gallisepticum: A chronic respiratory disease that stresses the bird. Detailed pathology from the Center for Food Security and Public Health confirms that MG infections can lead to pale or abnormal eggs.

Preventing Disease: Implementing strict biosecurity measures, such as limiting visitors and quarantining new birds, is essential to keep these pathogens away from your laying hens.

Symptom Checker: Is it Diet or Disease?

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Action Needed |

|---|---|---|

| Soft egg + Sneezing/Coughing | Infectious Bronchitis or Mycoplasma | Isolate & Consult Vet |

| Soft egg + Pale Comb/Lethargy | Mites, Lice, or Internal Parasites | Check for mites, Deworm |

| Soft egg + Healthy Hen (Single Bird) | Genetic Glitch or Age | Monitor |

| Soft eggs + Multiple Hens + Color Loss | Egg Drop Syndrome (EDS) | Consult Vet |

| Soft eggs + Hot Weather | Heat Stress | Add Electrolytes & Shade |

| Soft eggs + Thin Shells (Flock-wide) | Calcium/Vitamin D Deficiency | Adjust Diet (See Below) |

6. Age-Related Factors

Age plays a huge role in egg quality.

- Young Pullets: When a hen first starts laying (around 18-22 weeks), her reproductive system is like a new engine; it might misfire. It is very common to get a rubber egg or a double-yolker in the first month of laying. This is usually not a health problem; she is just calibrating.

- Older Hens: After 3 or 4 years, a hen’s shell gland naturally becomes less efficient. She produces larger eggs, but has the same amount of calcium to cover them, resulting in thinner shells.

7. Genetics and Individual Hen Factors

Sometimes, it is just bad genes. Some hens have a naturally defective shell gland. If you have 10 Rhode Island Reds eating the same feed, and only one consistently lays shell-less eggs while looking perfectly healthy, she likely has a genetic glitch or a physical defect in her oviduct.

8. Mycotoxins in Feed (Hidden Danger)

Sometimes the feed itself is the enemy, even if the nutritional label looks perfect. Mycotoxins are toxic substances produced by fungi (molds) that can grow in grain before or after harvest.

The Invisible Threat: I’ve learned to trust my nose. According to research from Kalmbach Feeds, these toxins can be present even in feed that looks and smells normal. Mycotoxins interfere with Vitamin D3 metabolism and calcium absorption, leading to soft or shell-less eggs. They can also cause lesions in the mouth and reduced feed intake.

Prevention:

- Buy from reputable companies: Ensure your feed supplier tests for mycotoxins.

- Storage: Keep feed in a cool, dry place and use a metal bin to prevent moisture and rodents.

- Freshness: Use feed within 30 days of opening.

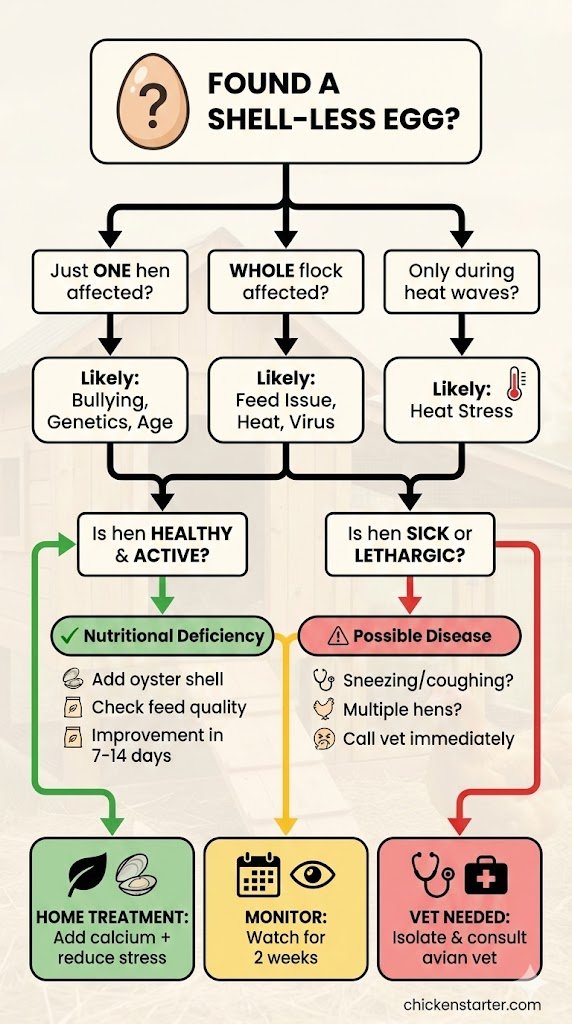

Diagnostic Guide: Identifying the Root Cause

Identifying the exact reason for shell-less eggs can be tricky. Use this decision tool to differentiate between a simple dietary fix and a more serious health issue.

Troubleshooting Flowchart: “If you see X, it’s likely Y”

- Check the Patient:

- Is it just ONE hen? -> Likely Bullying, Genetics, or Age. Check if she is being pecked away from the oyster shell feeder.

- Is it the WHOLE flock? -> Likely Feed Issue, Heat Stress, or Contagious Virus.

- Check the Symptoms:

- Healthy Behavior + Soft Shells: -> Likely Calcium/D3 Deficiency or Heat Stress. The hen acts normal but lacks building blocks.

- Sick Behavior (Sneezing/Lethargic) + Soft Shells: -> Likely Infectious Bronchitis or Egg Drop Syndrome. This is a medical issue, not just nutritional.

- Check the Environment:

- Hot Weather (>85°F)? -> Likely Heat Stress. Panting dumps carbon dioxide, altering blood pH and stopping shell formation.

- Recent Scare (Dog/Storm)? -> Likely Stress. The egg was expelled prematurely.

- Old Feed (>30 days)? -> Likely Mycotoxins or Vitamin degradation.

Comparison: Is it Nutritional or Viral?

It is crucial to distinguish between a hungry hen and a sick hen. This table highlights why a case might look like calcium deficiency but is actually a disease.

| Feature | Nutritional Deficiency | Viral Disease (EDS/IB) |

|---|---|---|

| Hen Behavior | Active, alert, normal appetite | Lethargic, huddled, low appetite |

| Respiratory Signs | None | Coughing, sneezing, gasping, discharge |

| Egg Appearance | Thin/Soft shells, often rough | Misshapen, wrinkled, pale (color loss) |

| Response to Calcium | Improves in 7-14 days | No improvement with calcium alone |

| Spread Pattern | Affects heavy layers first | Spreads rapidly to whole flock |

Expert Insight: If you see respiratory signs (sneezing), adding oyster shell won’t help. You need to isolate the bird immediately to prevent the spread of infection and focus on supportive care.

Can You Eat an Egg Without a Shell? Safety Considerations

This is the most common question I get: “Is it safe to eat?”

Is a Shell-Less Egg Safe to Eat?

The short answer is: Proceed with extreme caution.

Generally, if you find a fresh shell-less egg that is clean and intact, the yolk and white are technically edible. However, the hard shell is the egg’s primary defense against bacteria. Without it, the porous shell membrane is the only barrier.

- Salmonella Risk: Bacteria can penetrate the membrane much faster than a hard shell.

- Contamination: These eggs often break in the nesting box, mixing with poop and pine shavings.

My Rule of Thumb: In my kitchen, if an egg is laid in poop or looks dirty, I throw it away immediately. It is simply not worth the risk to my family’s health.

Proper Handling for Shell-Less Eggs

If you catch the egg immediately after it is laid (it is still warm and clean) and you want to use it:

- Refrigerate Immediately: Do not leave it on the counter.

- Cook Thoroughly: According to the FDA’s egg safety guidelines, you must cook eggs until both the yolk and white are firm. The FDA specifically recommends cooking casseroles and other dishes containing eggs to 160° F.

- No Raw Uses: Never use these for mayonnaise, caesar salad dressing, or sunny-side-up eggs. For more details, refer to UConn Extension’s guide to egg safety.

Shell-Less Egg Treatment: How to Fix the Problem

If you are dealing with this issue, simply “waiting and seeing” often isn’t enough. Here is a proven, step-by-step treatment protocol I use for nutritional shell issues, based on a specific challenge I faced with my own flock.

Case Study: Saving Henrietta’s Shells

A couple of years ago, my favorite Buff Orpington, Henrietta, started laying soft-shelled eggs every single morning for three weeks straight. She was acting fine, but the eggs were a mess. I was worried it was a disease, but since she was the only one affected, I suspected she was being bullied away from the oyster shell feeder.

Here is exactly what I did to fix it:

- Isolation: I moved her to a large dog crate inside the coop at night so she could eat without competition.

- Super-Dose Calcium: I added a liquid calcium supplement to her water for 3 days to get immediate absorption.

- Diet Reset: I cut out all kitchen scraps for the whole flock to ensure they were eating their nutrient-dense layer pellets.

The Result: On Day 4, she laid an egg with a rough, sandpaper-like shell (a sign of excess calcium deposits; it was working!). By Day 10, her shells were perfectly smooth and hard again. It turns out she just needed a nutritional reset without the stress of fighting for food.

Phase 1: Immediate Nutritional Reset (Days 1-3)

Goal: Quickly restore calcium levels and stop the “calcium drain” from the bones.

- Isolate the Hen (Optional but helpful): If only one hen is affected, placing her in a dog crate or separate coop allows you to monitor exactly what she eats.

- Switch to 100% Layer Feed: Remove all treats, scratch grains, and table scraps. These dilute the nutritional balance essential for laying hen nutrition. If you’re looking to upgrade your flock’s nutrition, see our reviews of the best organic and non-GMO chicken feeds that provide optimal calcium and vitamin D3 levels.

- Offer Free-Choice Calcium (Crucial Step): Place a small bowl of crushed oyster shell or limestone grit in the coop.

- Dosage Strategy: While you cannot force-feed grit, aim to make 1-2 tablespoons of crushed oyster shell per hen available daily in a separate feeder. Not sure about the difference between grit and oyster shells? Learn when chickens need each supplement and why.

- Refusal Trick: If your hen ignores the calcium, do not mix it into the main feed (they may pick around it). Instead, mix 1 teaspoon of oyster shell into a small amount of plain Greek yogurt or scrambled egg. The protein entices them to eat the calcium.

- Why Particle Size Matters: Mississippi State University Extension emphasizes that “Calcium is the primary mineral that makes up eggshells.” Due to its large particle size, oyster shell dissolves slowly in the gizzard. Since eggshell formation generally occurs around midnight, this slow release allows calcium to be available overnight when the bird isn’t eating, resulting in better shell quality than powdered calcium alone.

- Liquid Calcium Supplement (Emergency): If the shells are paper-thin, add a liquid calcium gluconate supplement to their water for 3 days. While long-term dietary changes are best, liquid supplements may offer a more rapid boost than solid calcium sources by bypassing the mechanical breakdown needed in the gizzard, though long-term peer-reviewed data on their superiority is limited.

- Product Guidance: Look for water-soluble poultry supplements (often labeled as “Hydro-Hen” or “Poultry Cell”) that specifically list Vitamin D3 in the top 5 ingredients.

Phase 2: Stabilization and Observation (Days 4-10)

Goal: Maintain intake and monitor shell quality improvements.

- Check Feed Quality: Smell your feed. Does it smell musty or sour? If so, throw it out (suspect mycotoxins) and buy a fresh bag.

- Monitor Droppings: Ensure the hen isn’t having diarrhea, which can prevent nutrient absorption.

- Check for Parasites: Inspect the vent area for lice or mites at night with a flashlight. These parasites suck blood and cause anemia, which creates stress factors that ruin egg quality.

Timeline for Recovery: Research indicates that correcting calcium intake provides a “quick remedy” that typically restores eggshell quality within a short period. While shells may harden sooner, it typically takes 10-14 days to fully replenish the hen’s medullary bone calcium reserves, according to commercial layer management guides.

Phase 3: Maintenance & Decision Making (Day 11+)

Goal: Prevent recurrence or escalate to medical care.

- Stop Emergency Supplements: Once shells harden (usually day 10-14), discontinue the liquid calcium/vitamin water additives. Excess Vitamin D can actually damage kidneys over long periods.

- Maintain Oyster Shell: Keep the dry oyster shell bowl full forever. It is cheap insurance for calcium carbonate supply.

- Reintroduce Treats: You can bring back treats, but keep them under 10% of the total diet to maintain proper phosphorus balance. Learn which kitchen scraps are safe for chickens and which to avoid to maintain proper calcium balance.

Troubleshooting: What If Treatment Fails?

If you have followed the protocol and are still seeing soft eggs, use this guide to pivot your strategy.

- Scenario A: 7 Days of Calcium, No Change.

- The Fix: Verify Vitamin D3. Calcium is useless without D3. If your flock is confined indoors, they likely have a Vitamin D3 deficiency. Add a specialized D3 supplement immediately.

- Check Feed Sorting: Are your hens picking out corn kernels and leaving the powdery minerals at the bottom of the feeder? Switch to a pellet or crumble feed to prevent sorting.

- Scenario B: Shells Improved, Then Got Soft Again.

- The Fix: Check for Red Mites. These nocturnal parasites cause anemia (calcium loss). Inspect roosts at night with a flashlight. Mites can drain a hen’s resources faster than you can replace them.

- Scenario C: Hen Refuses to Eat Oyster Shell.

- The Fix: Switch sources. Some hens prefer limestone grit over oyster shell, or vice versa. You can also try baking and crushing your own eggshells (fed back to them), as the smell is familiar and enticing.

Reality Check: A Failed Attempt (My Experience)

The “More Is Better” Mistake

Years ago, I had a Leghorn hen named “Speckles” who laid soft eggs. I assumed she just needed more calcium, so I drenched her feed in oyster shell dust and put calcium in her water daily for a month.

The Result: Not only did her shells not improve, but she developed kidney distress (visceral gout) from the calcium overdose. It turned out she had a genetic defect in her shell gland that no amount of mineral could fix.

The Lesson: If the protocol doesn’t work in 14 days, stop escalating the dosage. Sometimes biology wins, and “more” is not the answer.

Treatment Decision Tree: When to Worry

- Day 1: Found soft egg. Action: Start Phase 1 (Oyster shell + D3).

- Day 7: Check progress.

- Shells harder? -> Continue Phase 2.

- No change? -> Verify feed freshness and check for heat stress.

- Day 14: Final assessment.

- Problem solved? -> Move to Phase 3 (Maintenance).

- Soft shells continue? -> SUSPECT DISEASE.

Critical Rule: If soft shells continue after 2 weeks on oyster shell and fresh feed, the cause is likely not nutritional. You should suspect a viral infection (like Egg Drop Syndrome or Infectious Bronchitis) or a reproductive defect and consult a veterinarian.

Supportive Care for Viral Diseases (EDS/IB)

If the decision tree points to disease (multiple hens affected, respiratory signs), antibiotics will not help because these are viral infections. Instead, follow this nursing protocol:

- Strict Isolation: Move sick birds to a warm, dry dog crate away from the flock to stop the spread.

- Hydration with Electrolytes: Viral infections cause fever and dehydration. Add poultry electrolytes to their water to maintain blood chemistry.

- Soft Food Diet: If hens are lethargic, feed a “mash” of layer pellets mixed with warm water and a little applesauce. The soft texture encourages eating when they feel weak.

- Reduce Stress: Keep the isolation area dark and quiet. Stress suppresses the immune system, which needs to fight off the virus naturally.

Stress Reduction Strategies

If nutrition isn’t the issue, look at their environment.

- Cool the Coop: In summer, provide shade, ice water, and ventilation.

- Stop the Bullying: If one hen is guarding the food, add a second feeder out of sight of the first one.

- Secure the Run: Ensure predators cannot harass the birds at night.

When to Consult a Veterinarian

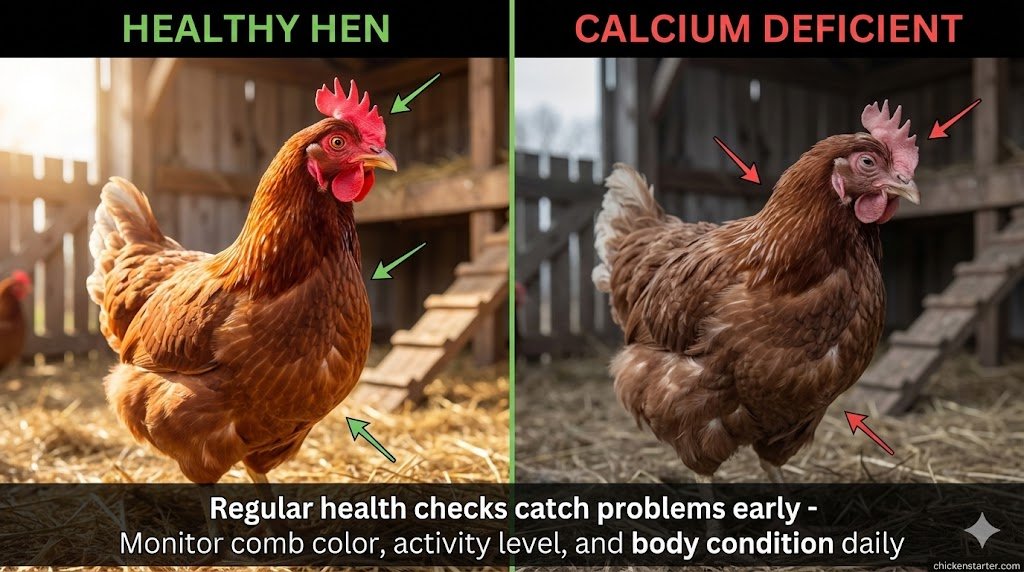

Before calling a vet, perform a complete health check on your hen to document symptoms. You should call an avian vet if:

- You see soft eggs from multiple hens at once (suggests contagion and possible need for biosecurity measures).

- The hen looks sick (droopy wings, closed eyes, labored breathing).

- You see blood on the egg or the vent area.

- The problem persists for more than 3 weeks despite the Phase 1 & 2 interventions. For a complete guide on recognizing emergency situations versus minor issues, read our article on when to call the vet for your backyard chicken.

Preventing Future Shell-Less Eggs: Long-Term Solutions

Prevention is always cheaper and easier than treatment. A robust prevention strategy requires looking at the calendar, your specific breeds, and the age of your flock.

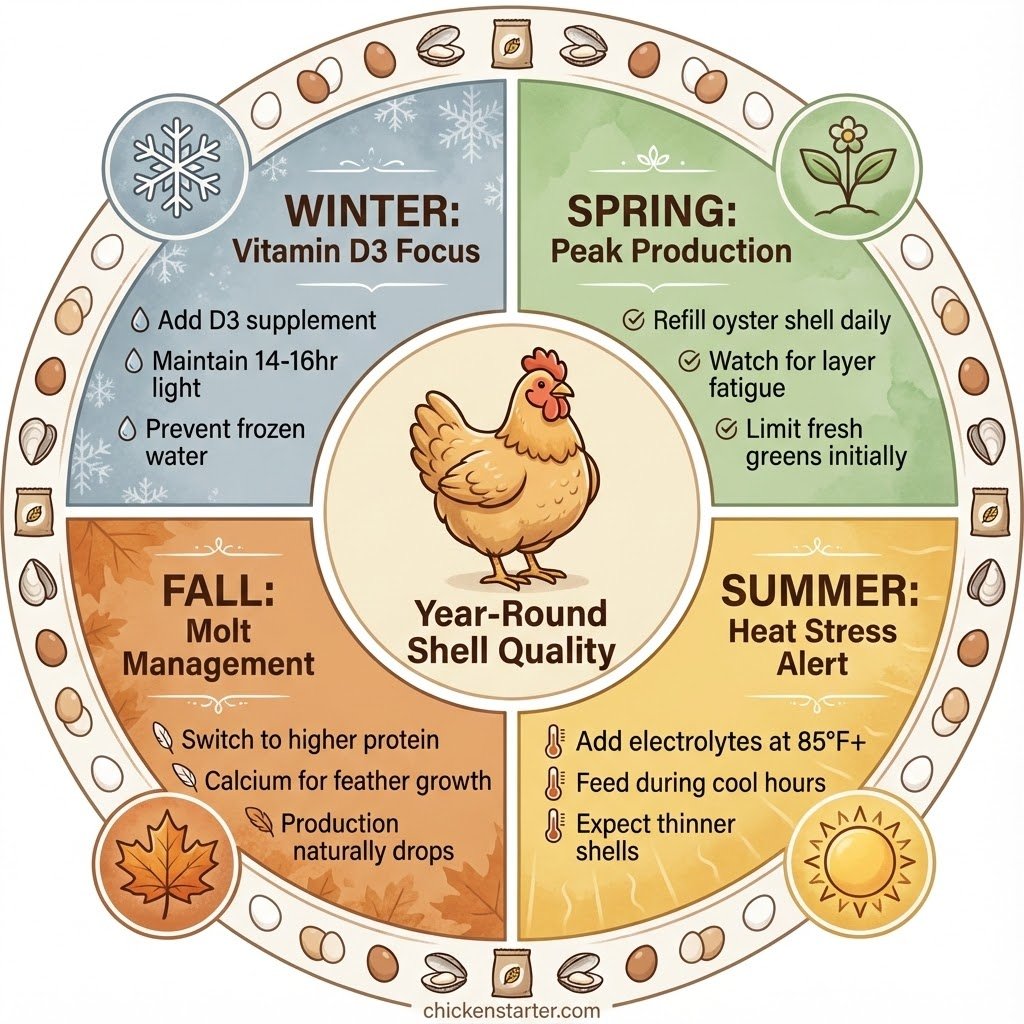

Seasonal Egg Quality Checklist

Managing egg quality requires adjusting your care routine as the seasons change. I’ve learned the hard way that what works in April doesn’t work in August.

Spring (Peak Production)

- Challenge: Hens are laying at maximum speed, depleting calcium reserves rapidly.

- Action: Ensure oyster shell feeders are never empty. Check daily.

- Diet: Limit fresh spring greens initially, as they can cause loose droppings and reduce nutrient absorption.

- Monitor: Watch for “layer fatigue” (hens unable to stand due to calcium depletion).

Summer (Heat Stress Prevention)

- Challenge: Heat is a shell killer. When chickens pant to cool down, they change their blood pH (respiratory alkalosis), which reduces the amount of calcium in their blood.

- My Observation: During the dog days of August, I notice my shells get thinner even with oyster shell available. I’ve found that adding electrolytes to their water during heat waves is the only way to keep the shells hard.

- Action: Feed early in the morning or late at night when it’s cool. Add electrolytes to their water on days over 85°F (29-30°C).

- Timing: Ensure oyster shell is available in the evening so calcium is in the gut overnight during shell formation.

Fall (Molt Management)

- Challenge: Hens stop laying to regrow feathers. While they aren’t laying, they are still using resources to build new plumage.

- Action: Switch to a higher protein feed (18-20%) to support feather growth.

- Expectations: Post-molt eggs are often larger and have excellent shell quality because the hen’s reproductive tract has had a chance to rest and repair. Additionally, during chicken molting season, calcium reserves are diverted to feather regrowth, sometimes resulting in thin or soft shells even in younger hens.

Winter (Low Light & Cold)

- Challenge: Less sunlight means less Vitamin D3 synthesis.

- My Winter Mistake: One January, I covered my run with a tarp to block the snow, but I accidentally blocked all the sunlight too. Within two weeks, I had soft-shelled eggs. I learned that they need that UV light even in winter.

- Action: Ensure your feed has adequate D3 or add a water-soluble supplement. Use heated waterers to ensure birds never go thirsty (dehydration stops egg production instantly).

- Lighting: As mentioned by Oregon State University Extension, using a timer to maintain 14 hours of light helps regulate hormones, but ensure the bulb is full-spectrum to aid vitamin synthesis.

Breed-Specific Vulnerabilities

Not all chickens are created equal. Your prevention strategy should depend on who is in your coop.

- High-Production Hybrids (ISA Browns, Golden Comets, Leghorns):

- These are the “Ferraris” of the egg world, bred to lay 300+ eggs a year.

- Risk: They are highly prone to “burnout” and shell quality issues after 18-24 months because they simply cannot eat enough calcium to keep up with output.

- My Observation: My Rhode Island Reds are machines, but they are usually the first to show signs of calcium stress. By age 2, if I miss even a day of oyster shell, I’ll find a thin-shelled egg.

- Strategy: These birds must have free-choice oyster shell available 24/7. Do not rely on layer feed alone.

- Heritage Breeds (Orpingtons, Barred Rocks, Wyandottes):

- These lay fewer eggs (200-250/year) and take natural breaks.

- Risk: Lower risk of depletion, but higher risk of obesity which can cause reproductive issues.

- My Observation: My Orpingtons are lazy. Their issue isn’t usually thin shells, but rather stopping laying entirely if they get too fat. I have to watch their treat intake more than their calcium.

- Strategy: Limit treats to prevent fatty liver disease, which can interfere with egg production.

- Easter Eggers (Mixed Breeds):

- My Observation: Interestingly, my Easter Eggers seem bulletproof. They lay fewer eggs per week (maybe 3-4 compared to the RIR’s 5-6), but those blue/green shells are almost always rock hard. The lower production rate seems to allow their bodies plenty of time to recharge calcium.

Feeding for Shell Quality by Age

Your hen’s needs change as she grows.

- Pullets (0-18 Weeks):

- Protocol: Feed “Chick Starter” or “Grower” feed (approx. 1% calcium).

- Warning: Alabama Cooperative Extension warns that the high calcium in layer feed can cause kidney damage in young birds. Do NOT feed layer pellets or oyster shell to chicks.

- Active Layers (18 Weeks – 2.5 Years):

- Protocol: Switch to “Layer Feed” (3.5-4% calcium) once the first egg appears. Provide free-choice oyster shell in a separate dish.

- Senior Hens (3+ Years):

- Protocol: As hens age, their ability to absorb calcium from their gut decreases.

- Strategy: Older hens often benefit from a probiotic supplement to aid digestion and occasional Vitamin D3 boosts in their water during winter, even if they are eating the same diet as the younger birds.

Optimal Nutrition for Strong Egg Shells

Maintain a consistent diet. Switching feeds rapidly can cause hens to stop eating. Stick to a reputable commercial layer feed. I prefer crumbles or pellets over mash, as birds can’t pick out just the tasty bits and leave the minerals behind.

Environmental Management for Healthy Egg Production

- Space: Overcrowding causes massive stress. Ensure you have at least 4 square feet of run space per bird.

- Roosting Bars: Ensure roosts aren’t too high (over 2-3 feet) if you have heavy breeds. Jumping down from high roosts can actually cause eggs to rupture inside the hen if she lands hard.

Flock Health Monitoring

Keeping a simple log helps identify patterns before they become disasters. If “Henrietta” lays a soft egg every Tuesday, it might be a specific stressor. If the whole flock does it, check the feed.

Sample Egg Health Log

| Date | Hen Name/Breed | Symptom Observed | Possible Cause | Action Taken |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nov 12 | Henrietta (Orpington) | Soft shell, looked lethargic | Molting stress | Added protein to diet |

| Nov 14 | Flock | 3 thin-shelled eggs | Ran out of oyster shell | Refilled calcium feeder |

| Nov 20 | Penny (RIR) | Shell-less egg on roost | Night fright? | Checked coop security |

Frequently Asked Questions About Shell-Less Eggs

What is an egg without shell called?

The technical terms are shell-less egg or membranous egg. Colloquially, backyard chicken keepers often refer to them as rubber eggs, wind eggs, or soft-shelled eggs. These terms all describe an egg that has been laid with the membrane intact but without the calcified hard outer layer.

Can parasites cause shell-less eggs?

While parasites like mites and lice don’t directly cause shell-less eggs, severe infestations create extreme stress that can disrupt egg formation. Heavy parasite loads also reduce nutrient absorption. Learn how to identify and treat mites and lice on chickens to keep your flock healthy.

What are the symptoms of egg drop syndrome?

The primary symptoms are a sudden drop in egg production along with the appearance of pale, thin-shelled, or shell-less eggs in an otherwise healthy-looking flock. Unlike respiratory diseases where birds cough or sneeze, hens with Egg Drop Syndrome (EDS) usually appear normal and active. You might also notice brown eggs losing their color and becoming white.

How much does an egg without shell weigh compared to normal?

An egg without a shell typically weighs 10-12% less than a normal egg. A standard large egg weighs about 60 grams, while a shell-less egg usually weighs between 50-55 grams. This weight difference is almost entirely due to the missing calcium carbonate layer.

Why are my chickens laying liquid eggs?

Finding a “liquid egg” (yolk and white with no casing) indicates a severe malfunction where the egg ruptured inside the hen or the shell membrane failed to form in the isthmus. This is more serious than a soft-shelled egg and implies the hen has absolutely zero calcium reserves or has suffered a physical trauma. Immediate veterinary attention or isolation is recommended.

Can chickens die from laying shell-less eggs?

The egg itself is not fatal, but the underlying cause (like severe nutritional deficiency or disease) can be life-threatening. Additionally, soft eggs are harder for the hen to pass because the muscles cannot grip them easily, leading to egg binding. If a hen appears to be straining (penguin walking) without producing an egg, this is a medical emergency.

How long does it take to fix soft shell egg problems?

If the cause is nutritional, you should see improvement within 7 to 14 days of correcting the diet and adding oyster shell. Stress-related issues often resolve within a few days once the stressor is removed. If the problem persists beyond two weeks despite treatment, suspect a disease or genetic issue.

Can I prevent shell-less eggs in young pullets?

Not entirely, as this is often a biological rite of passage. When a pullet first begins to lay (around 18-20 weeks), her reproductive system is still maturing. It is very common to see “glitch” eggs, including shell-less ones, during the first month of laying. Support her with high-quality layer feed, but time is usually the only cure for pullet start-up issues.

Are shell-less eggs more common in certain breeds?

Yes, high-production breeds are more susceptible. Breeds like White Leghorns, ISA Browns, and Rhode Island Reds, which are bred to lay 300+ eggs a year, place a massive demand on their calcium reserves. Heritage breeds that lay fewer eggs typically have fewer shell quality issues because their bodies have more time to replenish calcium between eggs.

Should I separate a hen laying shell-less eggs from the flock?

Generally, no, unless she appears physically ill or is being bullied. Chickens are social animals, and isolation causes significant stress, which can actually worsen egg quality problems. Only separate her if you need to monitor her specific feed intake for a few days (as in Phase 1 treatment) or if she is showing signs of contagious disease like coughing.

Do all chickens in a flock lay shell-less eggs if one does?

Not necessarily. If the cause is nutritional (bad feed) or viral (EDS), you will likely see multiple hens affected. However, if the cause is genetic or a specific injury, only that individual bird will lay them. Monitoring your flock log helps distinguish between individual and flock-wide problems.

Conclusion: Healthy Hens, Healthy Eggs

Finding a shell-less egg feels like a failure, but it’s usually just a warning light on your dashboard. Whether it’s a simple need for more oyster shell, a hot summer day, or a young pullet figuring things out, most causes are temporary and treatable. By sticking to the basics of high-quality nutrition, reducing stress, and monitoring your flock’s health daily, you can get back to collecting those perfect, hard-shelled eggs. Remember, you know your birds best. Trust your observations, follow the protocols, and enjoy the rewarding journey of keeping a backyard flock.

Oladepo Babatunde is the founder of ChickenStarter.com. He is a backyard chicken keeper and educator who specializes in helping beginners raise healthy flocks, particularly in warm climates. His expertise comes from years of hands-on experience building coops, treating common chicken ailments, and solving flock management issues. His own happy hens are a testament to his methods, laying 25-30 eggs weekly.